Why Is the Internet Fantasizing About China?

As Western soft power declines, China-related memes are turning fantasy into a form of alternative world-building.

This essay is part of an ongoing series on “Orientalism chic,” which maps new forms of Asian cultural expression in a multipolar world.

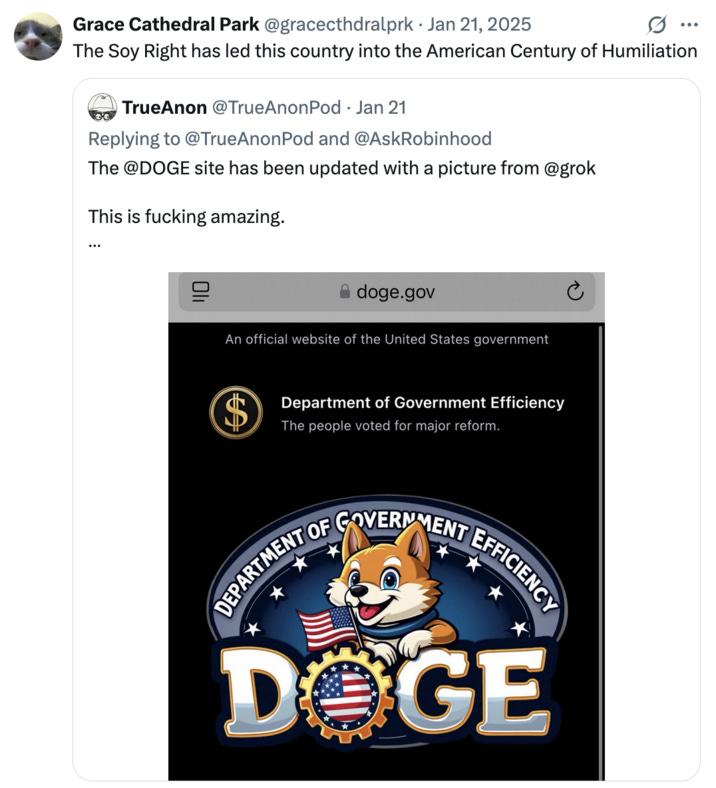

A tweet from January 2025 declares we are living in the American century of humiliation.

The post didn’t go viral by the usual standards on X, but according to Know Your Meme, it’s the first iteration in a larger, observable internet phenomenon: memes declaring the tone of the 21st century, otherwise known as the American “century of humiliation.”

Not until 2025 has the phrase “century of humiliation” appeared in the lexicon of the chronically online. Usually, it’s used by Chinese politicians to describe a hundred-year period in China’s history when the nation was subject to endless losses, defeats, and abuses by foreign powers. These include the loss of the Opium War and the cession of Hong Kong to the British; the ceding of Outer Manchuria to Russia in the Aigun and Peking treaties; and the Eight-Nation Alliance invasion to suppress the Boxer uprising. The “century of humiliation” ends by the Second World War, but its final act is arguably the most brutal and traumatic: the Rape of Nanjing, where Japanese forces murdered 300,000 out of 600,000 civilians living in the city.

Never mind that no similar events are happening in the United States, under this alleged American “century of humiliation.” In the strict definitional sense, America has never been subject to abuses and controls by foreign governments since the beginning of the 21st century. The United States is the world’s leading economy, comprising over a quarter of global GDP. The US dollar is still the world’s reserve currency, while the largest companies—both American- and foreign-owned—are listed in exchanges like the NASDAQ and NYSE. And since 1812, no major international war has taken place on American soil. Are we really living in the American “century of humiliation”?

Obviously not. But what is undeniable now is that Western soft power is in a steep terminal decline. With the erosion of liberal democracy and rise of authoritarianism in North America and Europe, the idea of the “West”—insofar as the “West” is a classical, liberal postwar order led by America, steering the world unidirectionally towards progress—is dead, as Yancey Stricker argues in Real Review. The phrase “American ‘century of humiliation’” might not be technically correct, but in our current malaise where optimistic America-led progress narratives have wrung dry, it does capture the vibe nicely.

But while the space of what we aspire toward remains open, where are people looking? At least on the internet, the answer is China.

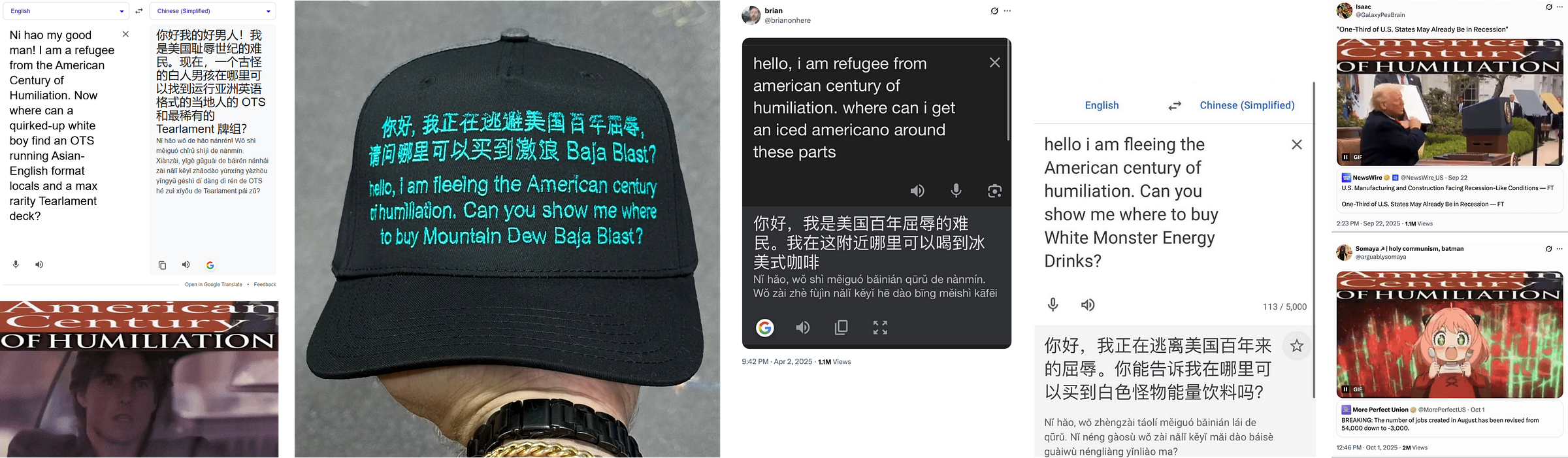

There is a growing collection of memes across platforms that fantasize a life that is Chinese. Westerners are “disappearing to China” at “9am on a Monday morning,” biking around cities like Shanghai to the sound of Mao Zedong’s propaganda song “Red Sun in the Sky.” European male models, scantily clad in cropped tops, raise their shirts to expose their stomachs and smoke cigarettes in a manner à la the Chinese uncle. The parody hip hop news account Daily Noud announced—and celebrated—the rapper Young Thug becoming Chinese.

“You met me at a very Chinese time in my life,” the netizens are saying; in one post, these words read against a view of Hong Kong’s skyline. Alternatively: “Daily affirmation: I am Chinese.” Another post written on Instagram Create mode reads: “At a certain point we just have to trust that the Chinese will save us. They have a lot going on over there. [S]omeone will probably figure something out.”

When a feigned desire to be Chinese, live like the Chinese, or live in China all consolidate on the internet, what does this amount to? It’s a collective desire for “libidinal catharsis,” says Bea Xu. “There’s a desire for escapism [from the West], for a fantasy for present day living conditions in Mainland China.”

Bea is a transdisciplinary artist based between Beijing and London, and she’s been closely tracking this new shift, archiving memes that project Western fantasies of life in China and Chinese identity. But the phenomenon’s origin story can be traced back to January 2025: just days before a proposed U.S. ban on TikTok, many American social media users “fled” to Chinese apps like RedNote as #TikTokRefugees.

“There was this hour-by-hour feed of cultural exchange on the platform where all of these Americans realized that China was more complicated, more relatable on the human level than they thought,” says Bea. “There was this sudden shockwave, but also a strange yearning and fetishism to escape to China.”

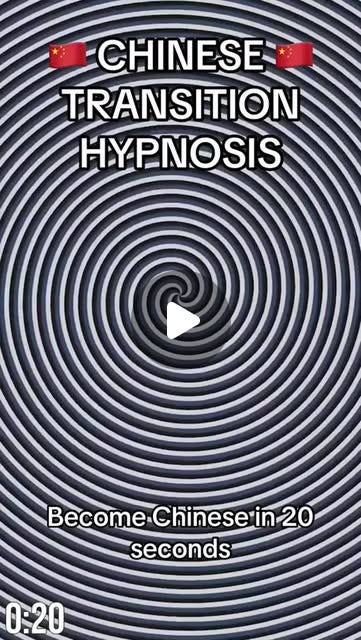

Since then, this new fetish for China and all things Chinese has continued to proliferate. Other memes in Bea’s archive include a video hypnotizing its viewer to turn Chinese, and a clip of a skinny white dude saying, “What’s up guys, next Friday is gonna be Chinese Friday!” With the rise of “absolute techno-capitalistic capture” in the West, Bea says, “There is a sad yearning for China and what it just symbolically represents as an alternative.”

“I think everyone knows in their hearts that this is just a fantasy,” she adds. “But might as well play into it anyway.”

As the blogger Minh Tran recently observed, “it has become passé to really stan East Asian countries where we have fully operational U.S military bases.” The neighboring, U.S.-allied Japan and South Korea feel almost Western, in the sense that they have their own authoritarian movements and late-stage capitalism speedruns. “The contrarian move is to pledge treasonous allegiances,” Tran writes. And one way that might take shape is by aspiring toward China as a reactionary fantasy.

In the American “century of humiliation,” no one really knows how we can imagine a better future. But for that, China is a convenient blank canvas. Such has often been the case for the nation in recent history. As the largest country in the world with a political and economic system fundamentally “other” to Western liberalism, China often represents an idea. Its national success forces the world to confront the possibility of prosperity outside capitalism and liberal democracy. It is a starting point for alternative imaginaries of all kinds, in creating stories and narratives for how the world should or shouldn’t operate.

For diplomacy hawks on Reddit, China is a looming economic threat in the “new Cold War.” For technocrat magazines like The Economist, China is a miraculous spectacle “dominating” global industry. For leftist streamers (one recent note is Hasan Piker), China is “dark woke” with an economic system the United States should “adopt and emulate.” And for AI Twitter, China is the harbinger of the tech-pocalypse. More often than not, these fantasies are more at home in the plane of dreams than in physical reality. The story is always extreme, always otherizing, often Orientalist, and never the more nuanced, complex reality of day-to-day life in Greater China: namely, that just like any country, there are costs and benefits to living here; that China possesses its own strengths to learn from, mistakes to avoid, and challenges that threaten its future trajectory.

For the new Chinese internet fantasy, China is Orientalism chic—here, the East is fundamentally “other,” but simultaneously cool and aspirational. And for artists and technologists like Bea, this kind of narrativizing on the internet can actually be productive.

In an essay for The New York Times, digital anthropologist Katherine Dee argues that the internet is a fairyland, a portal to another world. Where most see social media and web browsers as addictive drugs or sets of behavior, Dee sees “a place we travel to, with its own geography and customs.” It operates more like a magical plane, or “an otherworld with its own logic.” When science alone falls short in explaining ChatGPT-induced psychosis or how “For You” pages warp our perception of time, to see the internet as a strange, powerful, and mystical environment is to see it for what it really is.

To survive in this enchanted world, Dee argues, “we need the right kinds of stories to help us move through uncertainty.” To me, this underscores an important lesson: Internet fantasies, however misguided and illinformed, provide us a way in navigating the new world we find ourselves in. Can a fantasy of China help imagine an alternative future?

Indeed, it is harder to imagine a better world. But with or without memes, humanity is no stranger to creating fantasies that propel itself toward the future or into alternative realities. For TikTokers, it’s “manifesting.” For organized religions, it’s prayer. For accelerationists, it’s “hyperstition”—a concept developed by controversial far-right philosopher Nick Land to describe a self-fulfilling idea that becomes real through its mere existence. In all cases, something imagined becomes real through repetition.

Leaning into this impulse, the Chinese fanatics are correct, however underinformed they might be about on-the-ground realities in China. We need something—anything, really—to set our sights on the future, push ourselves towards the making of the new, rather than drowning in the dreariness of the present.

“I also felt the excitement of [these memes],” Bea says. And although it might be constructed from a Western imaginary, “I felt like I wanted to be carried by that fantasy.”

"We need something—anything, really—to set our sights on the future, push ourselves towards the making of the new, rather than drowning in the dreariness of the present."

Loved that line.

beautiful and timely article! lived in China for many years and wanted to gatekeep it so much, but at the same time wanted to tell everyone in the west how amazing China actually is... till I realized I could never convey how incredibly complex the reality is and how my experience as a foreigner would never compare to that of the locals. now I'm scared for when the internet discourse turns on China —because it will. Luckily, I don't think it'll affect them much.