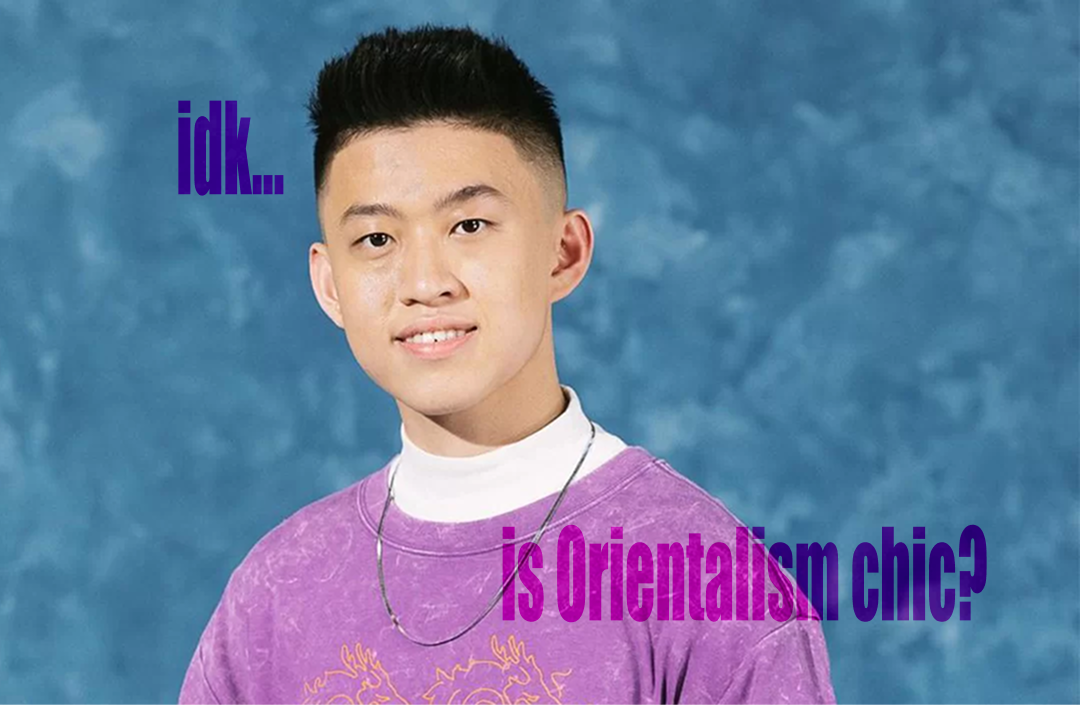

The Return of Orientalism Chic

In the mid-2010s, Asian musicians once sought recognition among Western artists. A decade later, they’re making difference aspirational.

I can remember exactly where I was and what I was doing the first time I heard a Rich Brian song. My friends and I were in freshman-year Chinese class, bored with the work that’d been assigned. The year was 2016, and we’d been hearing through the grapevine that a new Indonesian rapper was blowing up on SoundCloud. It was Rich Brian—then known as Rich Ch*gga—with a debut single titled “Dat $tick.”

Back then, the charts were dominated by mumble-rap trap artists like Migos, Lil Uzi Vert, and 21 Savage—Rich Brian’s debut single sounded nearly identical, except with the genre’s sounds and symbols uprooted from Los Angeles or Atlanta and transplanted straight to Jakarta with little to no changes. There were upbeat kicks, dark synthwave melodies, and choruses in the Migos-inspired flow that characterized most Western hip hop music of the decade. The music video was no less a copycat: praying hands, fake gang signs, and backup dancers waving around guns—several conventions of trap music videos from the 2010s.

Predictably, “Dat $tick” attracted plenty of ire—after all, this was the era of the #resistance. There were Twitter accusations of cultural appropriation and racism, and it probably didn’t help that one verse in the song included the n-word. Rich Brian apologized, of course. And long before he graduated from SoundCloud rapper to Real Musician, he had renamed himself more tastefully and stripped the name “Rich Ch*gga” from his brand entirely.

But I’m not here to sermonize. I think the more interesting story lies in Rich Brian’s attempts at mimicry—and what it meant for how Asia interacted with the world.

Looking back at these events nearly a decade later, Rich Brian’s efforts to copy Black artists underscored a common desire among popular Asian musicians: to be recognized among Western artists, to be seen by Western audiences, and to be defined by Western terms of success.

“Dat $tick” excelled at this. One compilation video shows the track being praised by then-popular artists like Desiigner, Tory Lanez, and even the mumble-rap king 21 Savage himself. With this newfound visibility, Rich Brian later signed with 88rising, an Asian-first music label, and began collaborating with artists like Joji, a Japanese American singer and YouTube comedian, and the Higher Brothers, a Chinese trap group from Chengdu. In 2018, the label released Head In The Clouds, which was sort of a magnum opus that fused pop, hip hop, and R&B by Asian artists specifically for Western audiences. The record was clearly designed to land easily on American ears, most of the songs were in English. Some Chinese rap verses from the Higher Brothers came and went, but still the flow was clearly inspired by Migos. The album became a moderate success, receiving favorable reviews on Highsnobiety and Pitchfork, with its lead single, “Midsummer Madness,” peaking in Billboard at #23.

Much of this era of Asian artists creating for Western recognition feels like ancient history, a product of a bygone era. Between 2016-2020, tensions between America and China brewed, but globalization had not yet reached its fever pitch, and there was a sense that some cultural bridge-building could allow peoples both Eastern and Western to reconcile their differences. Downstream of that were records like Head In The Clouds—they presented Asian cultural products as similar (if not identical) to Western culture. Hip hop, in turn, became understood as a shared tradition between Asia and America—and listening to the Asian variant over its Western counterpart was as simple as picking chocolate ice cream over vanilla. The message was clear: “Asian culture” (as vague and flattening a term as that may be) was not all that different from Western culture.

Art is, of course, life’s greatest imitator. And the era of cultural “bridge-building” and globalization-era optimism is long gone. Look at the escalating US-China trade war, the increasing difficulty to find jobs in the US or the UK as a foreigner, or the growing fears about a parallel, anti-Western global economy led by BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa), and the writing is on the wall: There is a growing divide between West and East that a hip hop album simply cannot solve.

How, then, are the highest levels of representing “Asian culture” changing? My thesis is this: It’s the return of Orientalism chic.

SKAI ISYOURGOD is one of few Asian musicians to achieve 88rising-levels of notoriety in 2025. SKAI is a Chinese rapper born in Huizhou, a city in southern China. You may have heard songs from his latest album Stacks from All Sides circulating across social media: as of writing in late October, a popular single like “Blueprint Supreme” is used in over 630,000 TikTok videos and 463,000 Instagram reels respectively. On Spotify, SKAI has around 4.2 million listeners, up from around 400,000 earlier this year.

The 88rising-era of Asian music found Chinese rap artists closely mimicking their Western counterparts. A VICE documentary on Chengdu trap—one of the country’s biggest rap subcultures in the 2010s—makes this obvious. The 17-minute segment depicts a number of Chinese rappers donning dreadlocks, waving gang signs, and enunciating verses with the same flow as Migos. When the VICE journalist asks a local musician “What is trap?” in Mandarin, the musician replies in English, and gives a clumsy half-answer that could be pulled from one of those Genius Lyrics explainer videos: “Yeah it’s music… trap is a lifestyle, you know what I’m sayin’.”

In contrast, SKAI’s discography is free of attempts to copy American styles. The Economist observes that “lyrics [in Stacks from All Sides] are often devout instead of dirty, somewhat closer to monk life than thug life… By contrast with boastful American rappers, on “Blueprint Supreme” he warns that ‘People obsessed with wealth have no sense of righteousness.’” And while SKAI says his discography is inspired by Memphis rap, you can’t connect his flow to any American contemporary. His verses sound less like “rap” per se, a friend of mine observed recently, and more so like an everyday enunciation of Mandarin in a Southern Chinese accent.

But the reason why SKAI’s music is so important is because it’s shaping the larger cultural imaginary around China—and Asia more broadly. “Blueprint Supreme” is used in restaurant promotional videos, in Chinese baby photoshoots, or in widely viewed TikToks and Instagram reels where Chinese (and other Asian) women hold phones with chopsticks. The latter echoes a 2018 Dolce & Gabbana campaign, where a Chinese woman clumsily ate pizza and a large cannoli with chopsticks—a campaign widely condemned as racist.

“Stacks from All Sides,” a darker, more brooding track with the same title as the album, is used in influencer content promoting Adidas in Beijing, by white male models aspirationally imitating Chinese uncles, and in videos depicting China’s rapid economic transformation over the last century.

Where I live in Hong Kong, Stacks from All Sides has acted like a de facto soundtrack-of-the-city over the last few months. Its singles are used by Hong Kong’s lifestyle creators with international audiences, and even in the Instagram stories of friends I follow. One video depicts a sort of opulent rich-kid lifestyle in the city alongside “Blueprint Supreme”: a yacht party, a night out in the main clubbing district, and scenes from the city’s colonial era members-only clubs.

I call this emerging language of representation “Orientalism chic.” The term is derivative of Edward Said’s Orientalism, describing the tendency for the West to present the East as mysterious, exotic, and fundamentally “other.” These representations are Orientalist because they cast an other-izing glow onto Greater China. Whether presenting Beijing-exclusive Adidas drops, Chengdu’s economic growth and urbanization, or lavish living in Hong Kong, life in these Chinese cities is differentiated fundamentally from the West. They are all chic because they are aspirational.

But the more interesting part of this emerging Orientalist, other-izing representation is that it is coming exclusively from Asians themselves.

Undergirding all of this is the central aesthetic force behind SKAI’s own music videos, which co-opt depictions that may have been considered “Orientalist” five years ago. One popular video features a sequence that fetishizes SKAI as a Chinese businessman/mob boss. In a later sequence, the rapper enters a dream, where he’s transplanted back to Qing-dynasty China, and berated by a man with a Fu Manchu mustache.

The era of 88rising leaned into assimilation and the desire to be liked under Western terms. But in the wake of deglobalization and a diverging East and West, these creators in Greater China are leaning instead into difference, into the other. They are leaning into Orientalism chic.

Self-Orientalizing in Asian countries is hardly a new phenomenon. In an essay for the Fashion Theory journal, anthropologists Ann Marie Leshkowich and Carla Jones traced a similar phenomenon in the 1990s. Then, “Asian chic”—or, Western reinterpretations of traditional modes of Asian dressing—grew popular in American and European fashion circles. These trends were not accurate to the original references. But as Asian chic’s popularity peaked, local designers in Asia started copying the Western designers who were copying them. For example, designers in Vietnam and Indonesia started mimicking (and selling) Western reinterpretations of the Vietnamese jacquard and the Indonesian sarong, even if they were originally derived from their home countries.

In essence, these local designers were borrowing Western imaginary of Asia, bringing it to their home countries, and making it cool. Orientalism chic, where Chinese people themselves are other-izing life in Greater China and presenting Orientalist depictions as aspirational, operates similarly.

One conclusion that Leshkowich and Jones make in their study is that spreading a cool/aspirational Orientalism “can be a privilege that enhances the status of those who employ it by signaling their familiarity with global discourses.” For Leshkowich and Jones, local designers bringing in Western remixes of local styles were often a part of an elite, globalist class in Asia.

This underscores another larger dynamic driving Orientalism chic. Orientalism chic similarly arises from elite, globalized tastemakers across Greater China, with its content primarily circulating on Western social media platforms.

As nativist sentiment in the West grows and working visas grow difficult for foreigners to acquire, the once globally-minded in Asia are reckoning with the fact that the West is not as easy for them to access, and that opportunities might be easier found close to home. More and more Chinese tech workers and creatives, for example, are returning to China en masse. And on the ground in Hong Kong, there’s a growing belief among friends that a life abroad—where your friends, communities, and support networks depend on a work visa—is a life built on borrowed time.

The old game of assimilation is no longer the meta. They must lean into difference, and recognize they are operating in a different world entirely. They must be Orientalism chic.

The way you discussed Orientalism Chic is very nuanced, but I fear that not many people will look closely at what you mean, and at the end, they only remember that Asian people are ok with Orientalism.

I believe that the phenomenon you're describing — Asian/Chinese people taking pride in their culture and even in the stereotypical/prejudiced versions of that — deserves a new name that has nothing to do with that term.

For example, the Adidas China drops were made because of guochao and how the younger generation are more culturally confident, that has nothing to do with Orientalism. SKAI uses a lot of Cantonese and regional references in his rap, his viral songs were created for himself and his homies, which might be responding to how mainland China celebrates regional cultures and dialects post-COVID, that has nothing to do with Orientalism.

Language dictates narratives. Using the term created by Western scholars, no matter what new meaning you give to it, continues to leave an impression that the individuals are observed through that outdated narrative.

I don't know what new term that might be, but I'm happy to continue the conversation!

Sometimes I wonder if liking and accepting the spread of very Chinese things in the West comes with too much optimism from Chinese people in China that Westerners will respect and understand the culture and heritage. And if you live in America, like I do, you know that’s a REACH.