The DJ Against the End of Globalization

Despite border closures and the rise of multipolarity, DJs are still connecting the world through spontaneous, informal networks.

You’d think that nearly thirty years after Hong Kong’s handover to China, British influence on the city is dormant. Edwardian-style architecture lines along the central business district, and every now and then you meet an alum of Harrow or Eton or another boarding school in Southern England. Blue-eyed British expats cluster around the International Finance Center, or “chic” districts like Sheung Wan, but now they are much fewer than before. Friends might speak in an accent that is at once British and American and Chinese, but because of Netflix and Instagram people have been sounding a lot more like a mix of the latter two.

This is the “British” in the former British colony of Hong Kong: persistent, still existing, but more so acting in the background rather than maintaining a continuous influence.

But the city’s nightclubs will tell a different story.

I’m lounging in a dimly lit room for a pregame at a friend of a friend’s apartment, sipping on a glass of whisky straight from the bottle. Some friends are circling around the kitchen island, drinking lemon chūhais and giggling about the latest scene gossip, but from the black velvet couch I’m seated on, the chatter is drowned out by the music playing in the background.

Terrence* and Sandy* are on aux tonight.1 But instead of controlling the speaker from an iPhone and a bluetooth connection, they’re spinning the decks—the friend of a friend has a DJ system plugged in his computer to mix tracks whenever he’s bored. The apartment is tiny, but the entire system controls two human head-sized speakers from an off-brand seller on Taobao. Sandy—a Hong Kong-born Korean—is teaching Terrence—a half-British-half-Chinese events organizer—how to DJ. I can vaguely make out what Sandy’s saying behind the chatter and the music, but since I’m not a DJ none of it makes sense to me.

“Pay attention to the bars,” Sandy says, pointing at the rekordbox app on the screen. “And make sure you time it right.”

Terrence looks dazed and doesn’t reply, so Sandy returns her attention back to mixing tracks. Warped bass and skittering breakbeats slowly fade into a woman’s howl—Sandy’s blasting “Rhythm ‘N’ Gash” by Rebound X, a track that I’d begun hearing around scene-y clubs on Saturdays nights since it went Boiler Room-viral earlier that spring. According to several YouTube netizens, the song is “possibly the best grime instrumental created” and basically “the English national anthem.”

Perhaps the choice of music was deliberate. We were killing a few hours before heading to a party in the Wanchai Harborfront where Conducta—a UK Garage DJ and the producer behind AJ Tracey’s hit song “Ladbroke Grove”—was set to play. He’d arrived in Hong Kong a week prior and, at one of the largest venues in the city, was sharing the decks back-to-back with scenesters Eugene and JUST BEE, two local DJs whose styles are characteristically British.

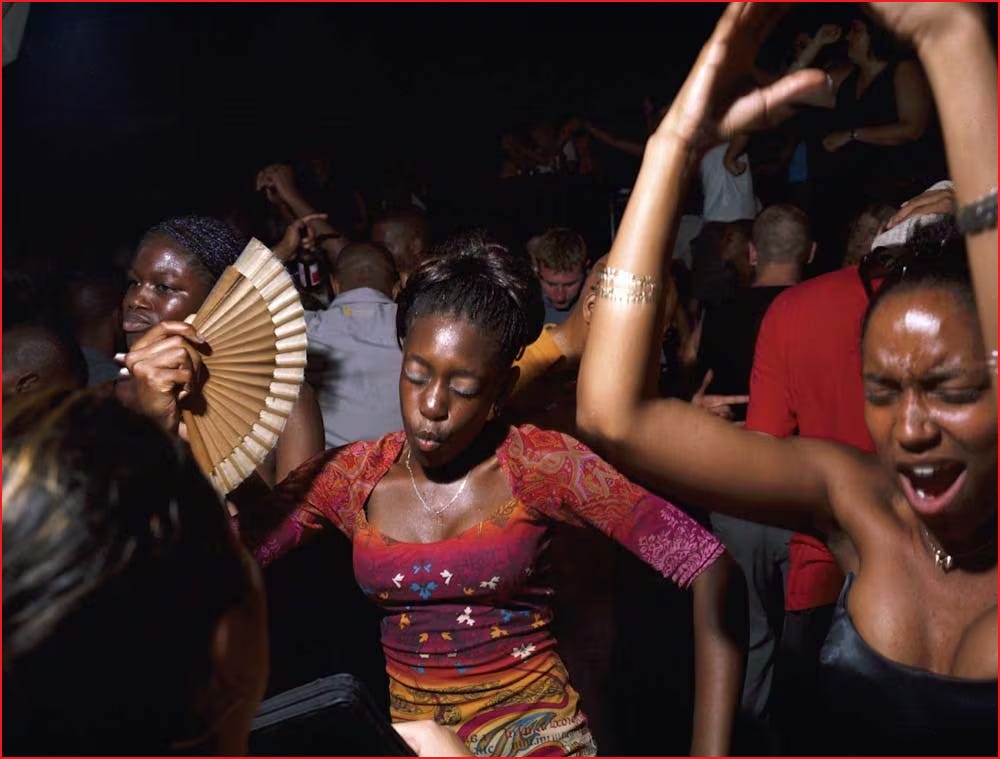

Thirty years ago and at the opposite end of the world, ravers would spill out of London’s Ministry of Sound Club at 9am, in search of Sunday morning after parties, where US house records would be played fast to keep weary dancers moving. These bright church-time events are where UK Garage was born: a “2-step” rhythm genre that the music journalist Simon Reynolds describes as “a distinctly British hybrid” between “house’s slinky panache [and] jungle’s rude-bwoy.” Fast forward to 2026 and the sound has evolved to often include warped basslines, syncopated hi-hats, skittering beats, as well as samples from UK Drill, with DJs like Conducta, Interplanetary Criminal, and Sammy Virji at the vanguard.

This kind of sound finds a home today in the clubs of Hong Kong, nearly 10,000 kilometers away.

“I actually had this conversation with guys like Conducta and Interplanetary Criminal… talk to them and one thing they all said was that they’re really shocked to see an audience for UK music in Hong Kong,” says Eugene, one of the DJs who had played with Conducta at that event, and with Interplanetary Criminal and Sammy Virji at other parties. “If you show someone in Hong Kong who’s never stepped foot in the UK to the clubs here, week after week they’re hearing UK music.”

“That by itself is a very borderless feeling,” Eugene adds. “They’re having fun, there’s entertainment, but they’re also getting to know the subculture.”

Few can empirically explain this phenomenon, but it’s not hard to formulate a likely hypothesis for why British music is so popular in Hong Kong. A kid from the city might go to college in London and return home with a tracklist from club nights at the Ministry of Sound. Or, an English teacher from Bristol might take on a job in Hong Kong, and in their spare time, inject themselves into the local scene and share UK club hits.

In the last few years, plenty of ink has been spilled on the DJ. Mixing tracks and controlling basslines is a new fascination, not only because of the viral DJ set as a popular internet medium, but also because DJs reveal features in our cultural milieu. For some, the DJ is symbolic of our culture’s obsession with remixes and “reheated nachos”—everything in film and television is a prequel or a sequel or a live-action remake. Or, for the writer Dani Offline, our obsession with DJs represents an obsession with taste in the information age, the ability to trawl through the slop and find great sound.

But can the DJ represent something else?

“Deglobalization” is one of the defining threads of the 2020s: working visas grow difficult to acquire, US-China tensions are rising, the global order that ruled the 20th century is disintegrating in favor of multipolarity. “[This is a] shift towards a world without effective collective governance, and where multilateralism is weakened by powers that obstruct it or turn away from it,” French President Emmanuel Macron warned in a speech at Davos this year. “And rules are undermined.”

But the work of a DJ seems to run counter to all of this. DJs actively fuse cultures, taking samples from disparate countries and combining them together into a final sonic product. One might recall the image of a chiseled ¥ØU$UK€ ¥UK1MAT$U: a shiny bald head mixing hyperpop from the American midwest with Chinese folk techno and verses from Palestinian jazz singer Nai Barghouti, all from a nightclub in Tokyo.2

“I think that’s the most fun thing ever,” says Eugene. “When you’re listening to a set and you’re hearing a heavy, dark German techno track, and the next track is Daft Punk, it does something to your brain. For me, I light up when that happens.” The DJ is not constrained by genre. No two tracks are too different to mix, and in the world of sound, no border is too towering to cross.

Landmark, a mall in the center of Hong Kong, captures the city’s globalist aspirations: in only 24,000 square meters, it compresses stores for almost every global luxury brand in existence with 16 Michelin stars (only two of which belong to Chinese restaurants) and the offices of multinationals like Sotheby’s, Point72, and PwC. Here, the world collides, but you’ll find a similar—and more interesting—version of that story in the mall’s basement.

Tucked underneath a few escalators is FM BELOWGROUND, a radio station directed by DJ Arthur Bray. The space outside had just been renovated, with six brand new speakers embedded inside a gradient gray marble wall. Arthur is sitting on a stool inside the DJ booth, a small room with an iMac and brand-new cotton padding for sound insulation. A shelf hovers near the ceiling, with vinyls collected from record stores around the world in one section, and in another, circa-1990s covers of The Face mixed in with zines produced by Arthur’s music collective, Yeti Out.

“The great thing about running a radio station is being exposed to talented DJs that come in and share what’s in their USBs,” Arthur says. “You’re always discovering new stuff.”

Artists from around the world have graced the booth, from the Manila-based label transit records to the London-by-way-of-NYC house artist Karl Phenom. That makes FM BELOWGROUND difficult to categorize, but a similar observation can be made about Arthur’s style as a DJ. Some of his sets fuse “rap and rave” with more grassroots Chinese genres: “A Yeti Out sound is probably a mix of electronic music from our Western influence, because we started doing parties in East London,” Arthur says. “But then mixed with Chengdu rap, Tibetan rap, Yunnan reggae. All those influences are multiplied by our travels and curiosities on the road.” It’s somewhat of a “Silk Road mentality,” he adds, a convergence of East and West.

A “Silk Road” metaphor might be a fitting way to capture the world of a DJ. These vast trade routes from the Classical era to the Late Middle Ages transmitted knowledge, ideas, cultures, beliefs between nations, and birthed the borderless concept of “Eurasia.” DJs operate on a similar infrastructure: budget flights from Hong Kong to Tokyo to London, bookings made through Instagram DMs, local nightlife circuits receptive to global talent—an improvised, informal global trade system. Goods and people and culture flow between borders, but it’s DJs instead of merchants and sound instead of silk.

Now is a good time to mention that “Silk Road” is the inspiration behind Silk Road Sounds, a Hong Kong-via-London-based record label Arthur founded with his twin brother, Tom, that bridges “the sonic gap between the East and West.” But listen to a recent set from their monthly NTS show and that may be an understatement: the pair blends “Typhoon version” Cantopop with a Japanese DJ’s remix of Brazilian funk and the Slam Dunk anime OST. “We didn’t even prep that show,” Arthur says. “But it’s such an extension of me and my brother’s taste.”

New hybrid cultural fusions emerged as a result of the Silk Road. An image of Herakles, for example, transformed into Shukongoshin, the Japanese guardian of the Buddha, when the Greek hero’s story traveled eastward. The DJ, traveling across borders on an improvised infrastructure, creates hybrid forms of their own: They might be mixing French rap with Indian jazz “but the connection from rap to jazz to you is exactly what’s true to your creation,” Arthur says. “It’s just that you’ve been able to find these connecting loops in ways that make sense to you.”

“Silk Road Sounds [is] an extension of who we are, being half-Cantonese, half-British, but also our A&R process,” Arthur says. “Who do we work with? We’re not sitting at a long table with Evian bottled waters and looking at who’s gonna make us the most money. It’s literally people that we fuck with or jam with backstage. Or people we meet on tour at 3AM.”

The globalization we know—vaguely acronymed organizations (“UNESCO,” “WTO,” “WFP”) in The Hague—may be in decline. But for the DJ, another world remains open: “Some people wonder, how can you go to Thailand or Seoul and find people that fuck with what you do? For us, that’s just the way we always thought it was,” Arthur says. (A recent Fall/Winter Yeti Out tour, for example, spanned Macau, Singapore, the Maldives, Pattaya, and Saigon.) “We’ll go to a different city and somebody will be like, yo, you gotta hit this guy up, he’ll get you a gig. Growing up in a multicultural family, it was always possible to move the way we move. I think within these communities, you’re always gonna have people in different cities putting you on.”

While it’s true that UK music holds a lasting influence in Hong Kong, the exchange is hardly unidirectional. Halfway across the world, some DJs are dropping Cantopop (Cantonese pop) between sets at bars and clubs in East London.

One such DJ is Chris Cho, a recent London transplant and a member of the city’s growing Hong Kong diaspora. “If I only play songs from another city or culture, even if I have the best technique, best transition skills, I’d never be able to resonate because I’m not from there,” says Chris. “[As a DJ,] this doesn’t feel generous to me. If I have the chance to play outside of Hong Kong, I’ll absolutely share a song that can represent myself.”

People aren’t necessarily looking to be educated about a foreign culture on the dance floor, so Chris’ approach usually involves a build-up, careful timing, and then quietly inserting classics like Teresa Teng’s “香港之夜” [Hong Kong Night] or “我要你的愛” [I Want Your Love] by Grace Chang. It is a sound that reveals less about how the world evolves to be “global” after deglobalization, and more about what remains in the wake of a British empire in retreat: the movement of people from peripheries to imperial cores—Hong Kong or Lagos or Punjab to London—spawns other hybrid sounds.

Like Arthur, Chris’ sound resists neat categorization—his set with HÖR Berlin mixes Cantopop and UK Garage with dancehall and the siren sound from Kill Bill. But his style also gains a new dimension wherever he plays: “When music moves from city to city it never lands in the exact same way,” he says. “The crowd will give new meaning to the song.”

“[Now,] I’m trying to mix [Cantopop] with baile funk,” Chris says. “I think those two are a great combo. They make old school Chinese songs feel more dance-y and modern.”

That’s one example. But there are an infinite number of permutations for unexpected mixes between sounds, and fusions from cultures separated by borders: German hard bounce and Filipino budots, vinahouse and South African gqom. For Arthur, it’s “the unlikely blend of drum and bass with a rap track or drill beat.” Similarly, a recent Bandcamp release by Eugene mixes Gwen Stefani ska-punk with early UK jungle.

The DJ is the future of globalization—

—insofar as “globalization” is increasingly informal and unstructured. “We create in the daytime, we play and party at nighttime. In between, we’re doing radio shows. It’s just the way [DJs] live,” Arthur says. “We always like to connect the dots.” The new Silk Road is maintained by DJs exchanging music like traveling merchants, by budget airlines and gig bookings via DM, by spinning decks that converge disparate cultures into one, by hybrid forms left behind after imperial decline, or by sounds unfixed and dynamic in their meaning.

Yes, the world is disconnecting, retreating, growing further apart. But perhaps with the greater distance, we are also left with a world that expands; a world wider, larger, more vast. And for some DJs, there remains a naive and hopeful optimism that there are cultures still hidden from view, sounds yet to be surfaced, experienced, and heard.

Arthur remembers visiting Tibet, 10 years after Yeti Out began throwing parties. A promoter was running a festival in Lhasa, one of the highest major cities in the world. “[He told us,] I think you guys would be pretty on-brand because your crew’s called Yeti Out. And we believe in the Yeti up here,” Arthur says. “I remember seeing this rap group called The Black Birds. They all came out in traditional monk outfits, and all [started] rapping in a Tibetan dialect. Crazy shit. Chills in the back of my neck. I’d never seen anything like it before.”

“It was familiar in the fact that it was a 140 BPM trap beat. But the language … It’s not even really about the language,” he recalls. “It’s just like, are you good vibes? You know what I mean?”

Terrence and Sandy are modified identities based on real people.

Patrickkkk stop writing so well, I can't say everything is my favourite article of yours

i cannot wait to talk about this with you later (coworker bestie !) i, again thoroughly enjoyed this read and find it so fascinating and your perspective such a refreshing take in a world of discourse about DJs being oversaturared and overdone. (also loved Dani Offline’s article, i had shared that with friends when i first read it)