Stop Looking for “Community”; Start Searching for a “Scene”

Offering a new way to think about the loneliness crisis (and respite from the “community”-discourse-industrial-complex).

Some friends and I like to say that if you join your local creative arts scene, you’ll never have to watch a TV show ever again. Every weekend, there’s enough fresh canon material to rival an HBO series. Nightclub X might be hosting party Y on a given Saturday, debuting DJ Z—a newcomer to the scene. Or maybe: underground artist A starts dating event producer B after festival C, creating an unlikely alliance between the city’s “alternative” and “mainstream” creative circles.

Twice a year—once near the end of summer and another towards the beginning of Christmas—a large-scale event occurs and all plotlines from “the scene” converge. Maybe an international DJ will be arriving in town and playing at Soho House till 5AM, a scene-y nightclub will run out of investor money and throw a closing party, or an evening marketplace will aggregate the city’s most well known artists into a room in an industrial warehouse. Regardless of the substance, said large-scale event will bring all members of “the scene” together and act as a series-ending climax or a season finale.

The night begins and artists D and E are gossiping with DJ F at the bar—they’re all brainstorming a new creative project and debating whether or not it will succeed (new storyline). From the opposite end of the counter, G photographer is mad that H content creator keeps snubbing him, even though both have worked together several times before (conflict and eventual resolution). Writer J is taking a shit and, while in the bathroom, overhears that K nightclub owner just got shadow-banned on Instagram, destroying nearly half a decade’s worth of tireless brand management and shameless self-promotion (killed-off character). Word spreads through whispers on the dance floor that L magazine editor is a nepo baby and her latest issue is a desperate act to launder daddy’s money into clout (end of an arc).

Now, influencer friend group M is crowding the space behind the DJ booth, but model friend group N arrives to challenge. The fight gets a little violent, but not in the way you’d expect. Instead of throwing fists, groups M and N are desperately trying to “mog” one another: swaying hips or shining biceps in front of the video camera facing the DJ booth, vying for pixels in the eventual video shared on YouTube. The models win against the influencers, but not without a few casualties: O, group leader of N and former Balenciaga model, is mogged to death by P, a lowly member of M with less than 10,000 Instagram followers. P just had a sharper jawline. After the large-scale event—the season finale—O disappears from the scene, never to surface again.

Plotholes are filled. Old arcs end and new storylines emerge, characters die and new personalities appear. The archetypes are plenty: DJs fight to be the main character, events organizers quickly rise to fan favorites on account of actually doing the important work, content creators are the much needed comic relief. On the weekends, I don’t often feel the urge to spend ten precious hours binge-watching an entire season of a prestige TV show because maybe there’s a gallery launch event this weekend held by Q curator at makeshift studio R, and I, an occasional party reporter, desperately want to cover it. Reality is a lot more exciting when you treat it like fiction.

I’m obviously writing in hyperbole. And my experience in the Hong Kong scene is far more mutually supportive, open, and friendly than the last few paragraphs make it out to be. But in a hyper-online, stay-at-home world, there’s plenty of joy to find in entertaining yourself by dramatizing your base reality.

Not every young person feels this way. When the New York Times published a feature on New York City’s 2025 summer interns, it wrote that “[many are] hustling to realize a version of New York that had danced across their social media feeds”—brunches in the West Village by day, parties in the Lower East Side by night—but in “reality, after work they tend to pass out watching Love Island USA.”

By now, the idea that young people are not socializing enough and spending too much time at home has been beaten like a dead horse. Gen Z is on the internet more is doomscrolling more has fewer friends on average is spending fewer hours outside the house. What might be more nauseating than this discourse are the vague, lobotomizing platitudes thrown around in response: “we just need third spaces,” “yeah mom was right it really is that damn phone,” or “in order to have a village I need to be a villager,” declared like incantations that would magically solve the loneliness crisis.

But for me nothing is more unhelpful than the vaguest platitude of them all: You just need to find community.

The word “community” was inescapable in 2025. The general thesis that bringing people together would heal our collective loneliness crisis was repeated ad nauseam by a countless number of writers, influencers, and thought leaders. The idea is numbingly simple: have more communities, and we would have a functional society again. Fewer phone-brained teenagers with 11-hour screen times, and instead a more happy and fulfilled population.

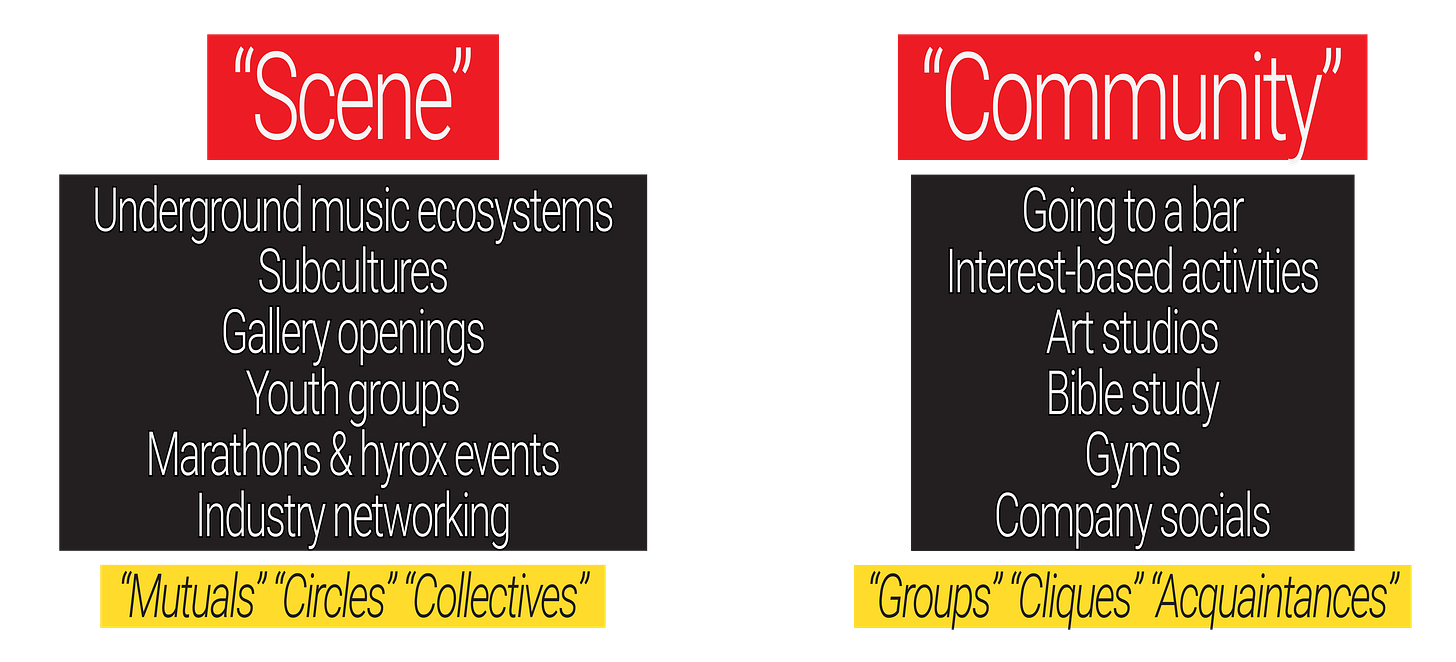

But today the word reads like a meaningless catch-all. “Community” is a nothing—it can mean anything from gyms to churches to discord servers, but also all the houses and stores on the same street, your political ideology, or people who all buy the same brand of clothing. And there’s often a more sinister assumption that lies behind the desire to just Get People Together and Call It a Day: that a happy, fun, unproblematic, uncomplicated group of friends with similar personalities to your own will eventually arrive to you on a silver platter.

That is, “we need communities to solve the loneliness crisis” severely misses the point—it assumes no contribution or effort on the part of the community seeker, and overlooks the uncomfortable truth that finding people who understand you requires work.

My 2025 began in limbo. I was reaching the tail-end of a transitional period, taking far longer than my family would’ve liked to figure out what I wanted to do after graduating from college. That usually meant spending my day juggling freelance assignments that failed to total towards a real income, and arriving home with a mix of dread and shame. I’d spend the rest of the night cooped up in my room, locking myself up with my own company. I saw friends regularly, but in droves, many had begun moving to other countries, beginning new chapters of their lives elsewhere.

I did at least end up channeling the solitude somewhere. With all the extra time by myself, I’d spend weekends typing from my computer at a cafe overlooking the harbor, sitting with my thoughts and a keyboard as I watched junk boats and pedestrians pass my view. I wrote a lot, and it was primarily through writing—releasing parts of my soul out into the internet’s vast ether—did I find new people to connect with.

I’m serious when I say that I met many of my recent friends from the internet. Doing the work and putting in the effort, contributing to the world and sharing a part of myself online, pulled me towards new worlds: to the local creative scene in Hong Kong, and to other scenes around the world. Writing pushed me into networks of people that understood me, to people whose interests were similar to my own.

I have a hunch that by zeroing in on “community,” we’ve arrived at the wrong solutions to the crisis of belonging in the 21st century. Perhaps: you don’t need to find “community,” you need to find a “scene.”

Scenes are extended universes. They are localized hotspots of activity that aggregate loose networks of people. Scenes can be a subculture, a network of artists and creatives in a city, but they can also describe interconnected religious youth groups, university student life, an industry with a surplus of networking events, or your extremely extroverted friend who mixes all of his friend groups into one.

Communities tend to imply fixed-ness—a fixed meeting time, fixed location, fixed group of people, fixed interests. Scenes are not so constrained: there are many people, many interests, many events happening at once, but all have a similar experience or principle (e.g. a creative scene is anchored around being creative).

Scenes also tether work, belonging, and identity to a wider cosmology. For example, you might know friend A because you were introduced by friend B, but maybe you connect with them a lot better because you’re both part of the same think tank circuit, or are in nightlife collectives that both play drum and bass. Scenes are the reason why your super washed uncle says college was the best time of his life: In a scene, you’re not a node within a single network; you’re linked to a larger web of intersecting sub-networks, with access to a wider universe of people to reach, know, and understand. Small fish big pond rather than big fish small pond.

Most importantly, you can only take from a scene as much as you give. For example, you’re friends with an event organizer precisely because you go to their events. As a DJ, you’re booked and invited to shows because you make great music, or, as an artist, other creatives are drawn to you for your sheer dedication to craft. Social networks in a scene hinge on an important principle: If you care enough about your own work, someone else will too.

It’s entertaining whenever new lore arrives at “the scene” at twice-a-year “season finale”-level events, but I’m honestly more impressed by the variety of people gathered together in one space. At one moment you’re dancing with a photographer who captures subjects with a Baroquian intensity. At another, you’re bumping into a post-internet art curator in the line for the toilet, or exchanging a cigarette with the first DJ in the city to ever play jungle. A friend of yours will be doing a vox pop for a local magazine; another is making you a yuzu-flavored cocktail while working the bar. We’re listening in on drama and tracking emerging storylines, but that’s all secondary to the larger mission at hand. We’re making a scene. We’re creating a new world where, together, we can belong.

I loved it

Loved this.