The Rise of Punk Globalism

Punk isn’t “dead,” but it’s changing to reflect a discontent unique to the 2020s.

The air coats in tar because all the windows are shut. Rooftop access, we’re told, is prohibited from the third floor. And twelve people have the genius idea to crowd around the building’s only fire exit, flick lighters and burn cigarettes with a large birch wood table and a woven wicker basket standing right next to them.

“Are we seriously going to be smoking around that?” my friend Henry* dryly says. “Zero fucking survival instincts.” I’m recovering from an overstaying cold—my nose is runny and my body still tired and for some reason my solution is to stand in a hotboxed fire exit in an industrial warehouse and drag Henry along with me.

We’d just listened to a twenty-five-year-old in a SCARFACE hoodie rap in screeching agony. His accent changed three times (from British to Chinese to American and back) throughout his thirty-minute set, while his friend, a shirtless, pudgy white guy, drummed in the background.

“Is that even legal?”

Henry and I turn around to the voice behind and see a short girl with bleached ‘man-repeller’-style eyebrows and a septum piercing thick enough for a cow. Here in Hong Kong’s Kowloon peninsula, she seemed fashion-forward, donning a short, inch-long fringe that you’d probably find in Berlin and carrying a tote bag from a North American hardcore band. “I heard that you’re only allowed to smoke indoors. Or you get fined $3000.”

Henry and I shrug because after years of living here that’s never been our experience. Septum Girl introduces herself to us as a brand-new transplant to Hong Kong—an art curator from Canada who speaks “少少” (very little) Cantonese. We all head back inside, returning for what we—Henry, Septum Girl, the smokers, and I—are here to attend on a Saturday night: a private concert at a secret location organized by Rice, one of the city’s leading punk music events organizers.

On social media, Rice is branded as “ur local youth outreach program.” But in a sea of pruning skin and salt-and-pepper hair, hardly anyone here seems that young. Only five people have the energy to take the mosh pit seriously. A young girl in the bottom left of my view is convulsing of her own initiative—but for the crowd of around fifty, everyone else is playing it safe, nodding heads to the guitar strums and standing still.

Last summer, someone lamented to me about a shocking number of Nazis in the punk scene, which is obviously horrible, but also really weird because I know a maximum of one Jewish person in the city. Who are the Nazis even picking a fight with at that point?

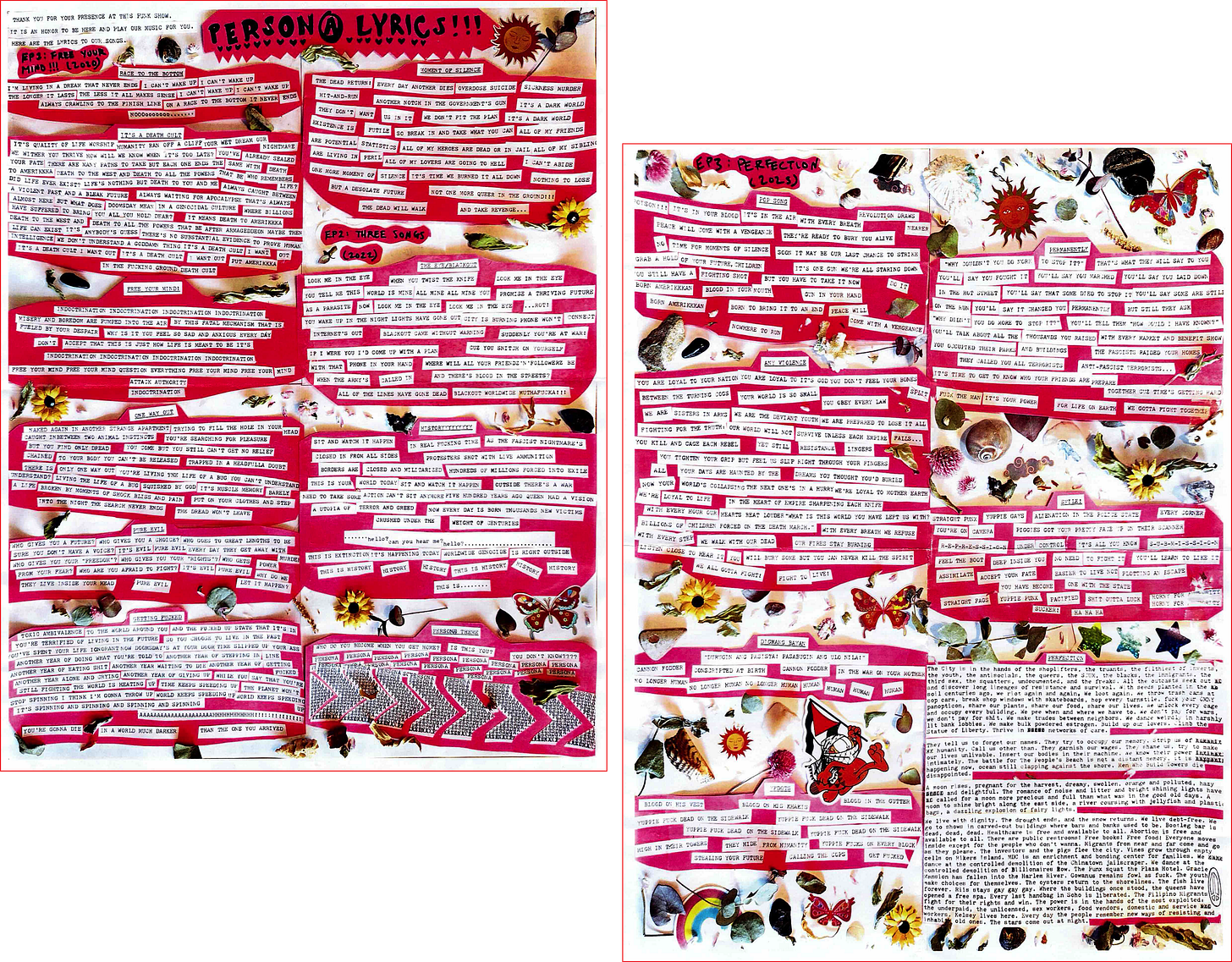

That means the Nazism is entirely a Western import. It’s a view not generated organically in Hong Kong, but instead a force that sprouts from 4chan’s dark corners and eventually lands on a local teenager’s Instagram explore page. And though its substance might be the most extreme polar opposite, you might also observe a foreign-ness about the event that Saturday night: PERSONA, a New York City-based “anarcho-punk” group, had just arrived in Hong Kong and was the evening’s final act. They were touring around Asia throughout January, hosting concerts in Batangas, Legaspi, and Manila (three different cities in the Philippines) and in Taiwan.

Just a few decades ago, the idea of a globe-touring “anarcho-punk” band may have been the target of finger-wagging accusations of hypocrisy. As David Simonelli traces in Contemporary British History, early punks were not the sort of crowd with the means to travel across continents, even if on a budget flight. In mid ‘70s London, for example, the movement catapulted first with working-class teenagers left unemployed during a recession. “There was little hope for a future in 1975 if you were young and working-class,” Simonelli writes. So what did they do? Channeled agony and transformed it into sound.

Punk was first a genre that mirrored economic malaise. Here, a DIY spirit, fondness for the shocking and the offensive, and anti-establishment views all fused to challenge traditional ideas of respectability and the monarchy that had failed them. For one, the lyrics of singer Johnny Rotten called on working-class youth to rebel against a society that had ignored their interests for too long. “There is no future / In England’s dreaming,” so goes the second verse in Sex Pistols’ classic punk song, “God Save the Queen.” “The working-class punk was unemployed because he could not find work,” Simonelli writes. “And punk was his angry protest against his lot in life.”

The lights turn on after the second performance, and it’s abundantly clear that the punk genre’s fans are a little different, now half a century later. From the crowd, I can make out the image of a man in a plain t-shirt from BEAMS Japan, the kind of retailer that someone generally buys to signal high taste, cultural fluency, and well-traveled-ness. People seem to belong to some kind of transient global class: at least a third of the concert-goers are white expats, and while lining up for the bathroom, someone nearby admits to attending one of Hong Kong’s most expensive high schools:

“He and I went to French International School, until I got kicked out,” I overhear one woman say.

Henry finds me once I step out of the bathroom to pull me aside and whisper, cynically, “Everyone here seems like a spoiled rich kid.”

There is a valid argument that something cannot truly be “punk” if its biggest proponents are not angsty working-class youth, but instead well-traveled millennials and privately educated Gen Zs. But debates about the purity of “punk” are as old as the genre itself. As early as the ‘70s, the same decade as the genre’s emergence, popular bands like the Sex Pistols and The Clash abandoned the independent labels for more lucrative contracts with large companies like EMI and CBS, calling their anti-establishment politics into question.

But, as Dick Hebdige writes in the seminal book Subculture: The Meaning of Style, “punk was forever condemned to act out alienation… to manufacture a whole series of subjective correlatives for the official archetypes of the ‘crisis of modern life.’” Put more simply, it’s not the reasons for punk-ing out that actually matter. You might be complaining about unemployment figures, the recession, surveillance capitalism, patriarchy, the rise of fascism, climate change, or, in 2026, the rise of AI—but substance is secondary to the fact that punk is an expression of discontent. “In punk,” writes Hebdige, “alienation assumed an almost tangible quality.”

You can still find traces of this sentiment in popular expressions of punk today. A few months ago, a video had been circling around of a band of young, shirtless, lanky American males, moshing in what looks like a spacious living room in a white-walled suburban home. The band featured in the video is literally named “Private School,” and the lyrics hint at a very specific white-collar malaise: “Coulda been a corporate motherfucker / But I’m this,” the band’s lead singer shouts into the microphone.

I’m inclined to think it’s not so much that punk has “changed,” is “dead,” has “lost its original spirit,” et cetera, and more so that the sources of discontent are changing. At least in global cities like Hong Kong or in the McMansions of the American suburbs, populations are (generally) fed and housed. But opportunities are scarce, and a life of stability is slipping from view.

“The traditional path to wealth accumulation is closed. Not difficult. Closed. When boomers hold ~50% of national wealth while comprising 20% of the population, and millennials hold ~10% despite being the same share [sic], the game reveals itself to be fundamentally broken,” reads a widely-shared X.com essay on young people’s diminishing prospects. “The implicit deal used to be simple: show up, work hard, stay loyal, and you’ll be rewarded… That deal is dead.”

There is a generation-and-a-half of people—people around my age or slightly older—raised entirely on zero-interest-rate period (ZIRP) optimism. During the long 2010s when money was free, opportunities were assumed to be in perpetual abundance. Budget airlines and e-commerce—brought to the world at scale through cheap borrowing—connected the world in ways we had previously never imagined. And life, we believed, would only improve linearly with time.

Of course, that has changed: deglobalization, a looming economic crash, a tightening job market, what have you. What remains is a collective sense of disappointment in a future that never arrived, a disaffection towards the reality we face instead, and plenty of no-longer-youths in desperate need for release. Events hosted by groups like Rice offer a peek into how this new “crisis of modern life” crystallizes: a “punk” might wear a BEAMS Japan shirt because they can travel across continents on Ryanair or AirAsia, but can’t get a job, afford a house, or raise a family.

The main event of the evening was actually quite a blur for me. I was getting a little more dizzy from the cold. Even from the video footage I recorded, I can barely make out the lyrics PERSONA’s lead singer was enunciating. But I do remember them whispering breathlessly into the microphone, saying “thank you everybody… it’s really important that we have these DIY communities to connect across borders.”

It’s hardly “punk” in the original sense. But when DIY communities connect across the globe, when discontent is expressed against a world where “you can survive but can’t get anywhere,” where punk concerts are attended by the worldly and the well-educated, what does it amount to?

For me, it’s “punk globalism.”

It’s the angst that remains after ZIRP-era optimism, from a worldly, globalized generation-and-a-half of people raised on a bright, prosperous future that failed to materialize.

Silly as “punk globalism” might be, there are signs it can be both useful and productive. It’s the punk spirit, after all, that pushed Rice to fundraise HK$21,000 for We Feed Gaza, an independent grassroots Catholic movement distributing food in Palestine, late last year.

“We are all living through a very dark period. With our own worlds full of problems, it may be easier to look away than to show compassion for others,” Rice’s organizers wrote on Instagram. “But one day, you may look back and wish you had done more when you could have.” In the words of Hebdige, it’s “acting out of alienation” against the “crises of modern life.” The original punk may not have been as well-traveled, but this new punk spirit, with its globalist tendencies, expands concern and action to new causes around the world that, in a previous decade, might’ve been left unseen.

Great read! Hebdige should be a must read for everyone writing about subcultures I feel like

The think global act local movement in action.