This Fashion Startup Wants Your Taste to Make You Money

OMEN is creating a new digital marketplace where cultural capital can convert into a liquid asset.

You’re currently reading THE CHOW, a newsletter on “the business of subculture.” This is a fully bootstrapped publication. If you’ve enjoyed my reporting or found it useful in any way, please consider upgrading to paid—you’ll get access to my zine library and help me keep this project running:

Edmond Lau stands in front of me, phone camera in hand. Recording, he asks, “What’s a good omen to you?”

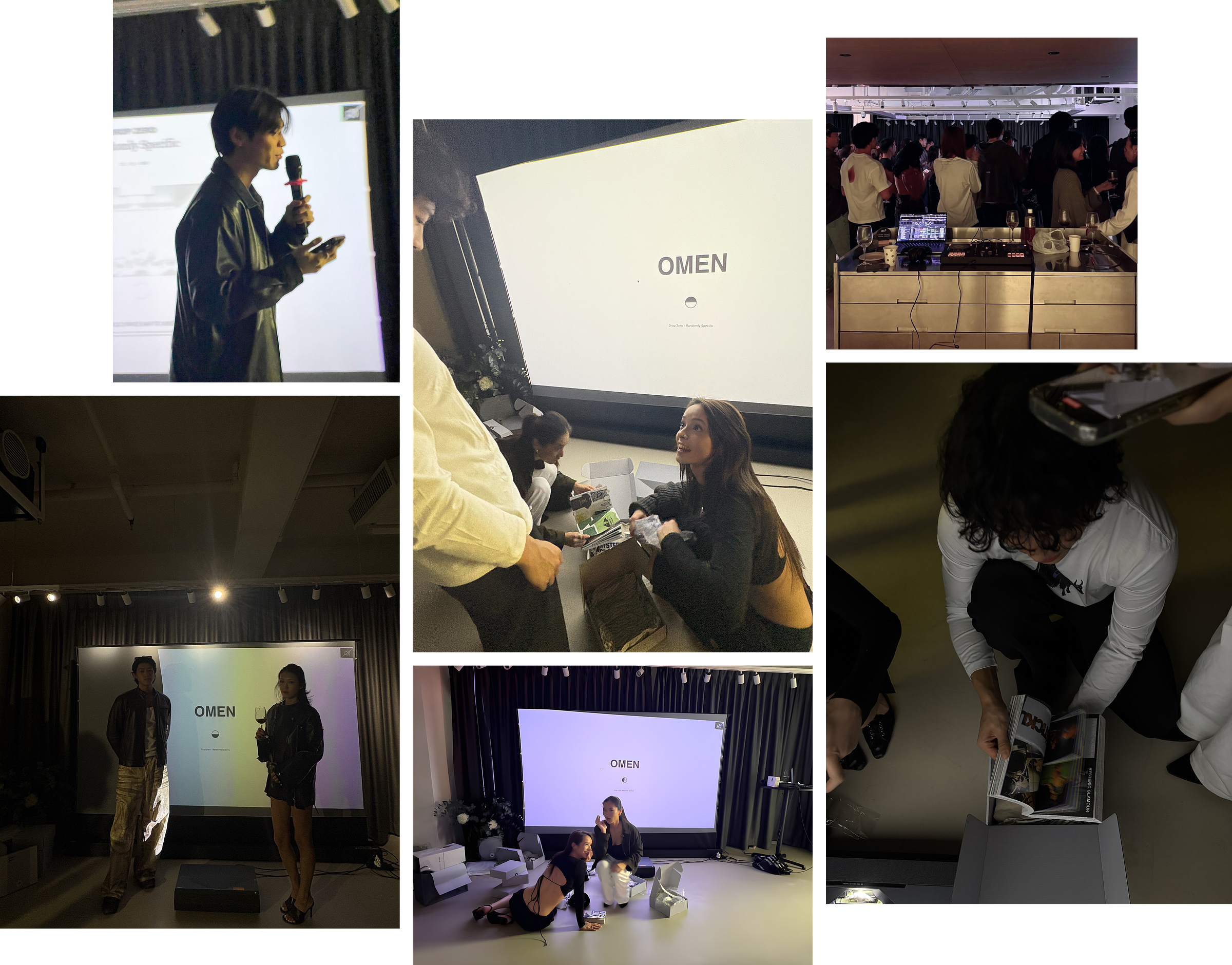

My mind runs blank for about five seconds before I make up a non-answer—I tell him I feel lucky when there’s “sunshine in the morning” or “when I’m hydrated.” Edmond stops the recording, and quickly disappears into the crowded party to ask other people the exact same question. Jerry Kwok, his friend and co-host at the event, is stationed at the natural wine bar, greeting people filing in.

It is the 21st of November, and if Chinese Calendar Online is correct, it is an “auspicious” day for a “grand opening.” Inside a private event space in Hong Kong’s Wanchai district, that is on Jerry and Edmond’s agenda: an opening party for their new fashion startup, OMEN.

The name, the pair say, signifies a new way to approach the very crowded fashion market: OMEN’s product is a “curated digital blind box” of fashion and lifestyle items. A venture capitalist might describe this as the Pop Mart for fashion e-commerce or the SSENSE of “gashapons” (random toy dispensers in Japan). After purchasing a blind box, buyers get an item manually curated by the OMEN team that could be worth more or less than the price of the actual box.

At around 9pm, the lights dim. Jerry tames the crowd to deliver a live demonstration of OMEN’s digital platform and of the unboxing process. One party attendee opens a curated box she had purchased in advance. She’s a professional photographer. And by some luck, her box contains a YSL Lomography Reloadable Camera.

“It’s rigged!” a friend of Jerry’s jeers from the crowd.

Jerry scrambles to explain himself, raising his hands in the air, saying, “It’s not, I promise! Ask our engineer!”

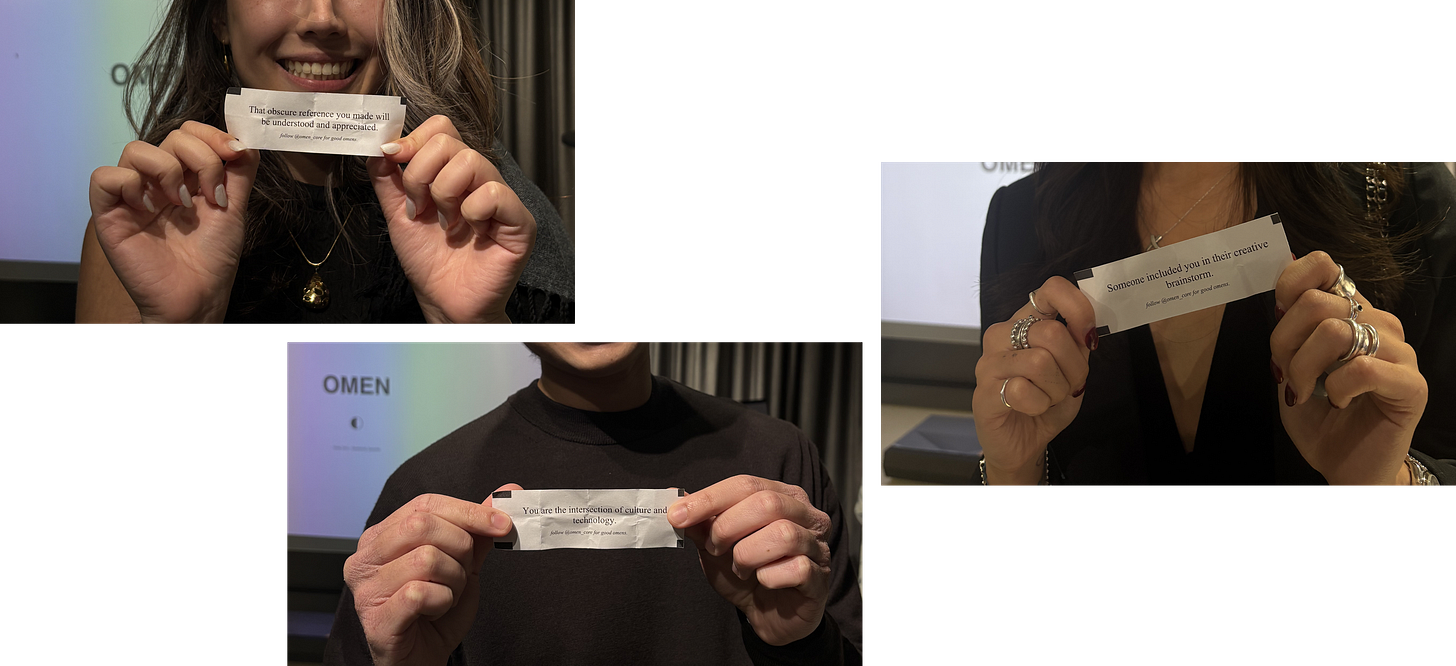

The whole episode might’ve been better clarified by one of the taglines scattered through OMEN’s web and social media copy: “The outcome may be random. What’s inside the boxes is anything but.”

“It’s almost oxymoronic. It’s random and specific,” Jerry, the brains behind OMEN, explained to me earlier that week. “Random in the sense that the blind box mechanic is random, but the curation is around a certain theme or aesthetic. I think that opens a fun way to discover items.”

For the last five years, fashion e-commerce has shifted towards hyper-niche-ficiation: social media algorithms silo users into distinct categories for advertisers, and everything is personalized to someone’s exact taste. The problem with that, the pair said, is that you’re stuck in an echo chamber. “You’re never surprised because you’re constantly being fed things you already like,” Edmond, who the Financial Times once dubbed a luxury memologist, added. “OMEN is a way to introduce serendipity within constraints.”

In the 2010s, friction played a huge role in lifestyle and fashion markets—in the lines-around-the-block to enter Supreme stores or the impossibility of snagging a pair of Yeezys. But with new payment technologies like Apple Pay and buy-now-pay-later schemes, it’s just too easy to buy something online. “When things come too easily, it doesn’t become memorable,” said Jerry. “[For OMEN], the friction comes in the financial commitment. It’s a commitment of uncertainty. I think that is something very under-explored in e-commerce and fashion.”

Edmond is a millennial cusp and Jerry is a pre-2000s Gen Z, two sub-generations that were raised on blind boxes, from Yu-Gi-Oh! and Pokemon card packs, to the digital cases in Counter Strike: Global Offensive. For kids who couldn’t go shopping without a parent, these served as taste signifiers and ways to express identity. “This mystery box mechanic has been around for years,” Jerry said. “Every game had some sort of blind box mechanic. When I thought of blind boxes and I saw the rise of Pop Mart, I thought, What if we can make this experience truly scalable?”

But while OMEN is primarily experimenting with blind boxes as a new distribution tactic, the startup is also a product of “the moment”—and it’d be remiss to gloss over the wider shifts that led Jerry and Edmond to launch the startup.

Less than a century ago, the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu famously theorized how economic capital and cultural capital were intertwined. Money financed and sustained artists, writers, galleries, and magazines, while the culture generated through this process provided the wealthy with the knowledge and taste signifiers that legitimized their wealth. At least, that’s the story often told in entry-level sociology courses.

But today’s elite seem to show little care for the taste signifiers that once legitimized them: Transplant Bourdieu to 2025, and he might jolt in horror at the way that new-money tech moguls like Elon Musk spend extra cash on AI-generated waifus or at the sheer volume of investments funneled into pseudo-gambling apps like Kalshi or PolyMarket.

Instead, as Kyla Scanlon reported in August 2025, a lot of money in the global economy is going to speculative investments and vibes-based meme stock trading. And while that’s not a system that an underpaid creative class might easily capitalize on, OMEN is trying to change that. “What we’re seeing now is a decoupling of economic and cultural capital,“ said Edmond. “What we wanted to do was experiment: How can we turn cultural clout into actual monetary capital?”

Though OMEN is primarily a curated fashion gashapon, another core product feature is the digital marketplace. While buyers can keep the physical items they receive from an OMEN blind box, using OMEN’s marketplace, they can also trade it, sell it, or maintain their ownership of it on their profile and decide what to do with it at a later date.

The latter function in particular serves to transform “taste” and curation into a liquid, tradable asset that increases in value. To illustrate: say a high-cultural-capital, low-economic-capital person unboxed a sold-out hoodie from a cult-status streetwear brand. On OMEN’s digital marketplace, they can instantly trade it at a premium.

“We’re trying to use digital ownership to make cultural capital lucrative,” said Edmond. “We’re aiming to surface and identify things before they emerge, and revive this idea that there is value in curation and in being opinionated.”

That ability to “curate”—to have opinions on whether a cultural product is aesthetically “good” or “bad,” on whether a piece of clothing is chic or cheugy—seems to be less and less common when so much culture is dictated by technology, when what we watch is dictated by algorithms on Netflix and YouTube, what we listen to by AI-generated Spotify playlists.

But among the OMEN team, there’s still a conviction that culture should set the agenda: “I always believed that technology should serve culture, not the other way around,” Jerry said. Most of it is abstracted away, but OMEN’s stack—the technologies that keep the marketplace and the digital blind boxes functioning—is built on blockchain. Collecting, trading, and owning the underlying asset is recorded permanently on chain, which Jerry said offers “immutable evidence of [a user’s] taste.”

Among the world’s amorphous creative class, the phrase “high taste, questionably employed” is often thrown around. It might describe “starving artists” like van Gogh and Monet who sit comfortably in the Western canon of art history, writers churning 2,500-word essays for a 300USD a piece, or freelance graphic designers with a long list of clients not responding to their emails. There’s a sense that these cultural workers operate in a plane where financial capital can’t seem to follow. And the “high taste, questionably employed” descriptor underscores a widely accepted idea: “taste” is the kind of sensibility that neither money nor traditional jobs can easily reward.

But the irony today is that, in the age of AI, where information flows in vacuous abundance, “taste” is said to be the last skill elevating humans above machines. The ability to sort through the garbage of the internet and find great culture is what will separate the winners from the losers in this new economy, the argument goes. The idea is growing in salience, appearing in viral Substack essays, in the writing of the world’s preeminent cultural journalists, and even among Silicon Valley’s tech elite. Case in point: venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, who once argued that ChatGPT would make creative work obsolete, said in May that AI will never replace jobs that require human taste.

Yet few have seriously provided a vision for how a “high taste, questionably employed” crowd will be adequately compensated, or where their cultural sensibilities might become financially advantageous.

But for OMEN, “taste” is at once a core product offering—a way to make money—and a skill they’re proving has real economic value.

At the launch party, other unboxed items included vintage items from Hysteric Glamour, clothing from the Japanese label Kapital, and sunglasses from Gentle Monster. Several items were handpicked by Jerry himself at the Dover Street Market in Tokyo, or during solo curatorial trips across Asia. There was wooing and cheering from the crowd—the first time in a while I’d seen real excitement over a curator’s work.

“Big tech is mining culture workers for their knowledge. These days, you have very culturally attuned people with very little to show for it,” Edmond said to me over our final follow up. “I want people like us to finally win.”

Amazing article as always, Patrick! As someone who definitely finds themself fitting the “high taste, questionably employed” descriptor (both as a cultural events organiser and as a freelance brand design consultant) I’ve strongly felt over time that the way cultural workers can benefit from the current landscape is to double down soft skills and capitalize on their way of thinking/perspective/taste. That is what sets us apart from machines who can only create from command and in the end is the essence of what (I think) will sustain cultural capital. Lovely to see Edmond and Jerry both feeling similar and paving a new way for creatives to benefit without shrinking themselves into constrained tasteless outdated systems that just serve financial capital.