A Return to the Craft

Forecasting the future of creative business from an open-air kitchen.

Gas is burning on a spinning wok. A man—sweaty, middle-aged, wearing a yellow tank top—mixes flat rice noodles, beef, and onion into a char. His brother, a sous chef on his left, is dressed down below the waist: donning oversized checkered boxers and a white, double-breasted jacket, he thrusts a butcher knife into the carcass of a freshly boiled crab.

From where I’m sitting, none of this hides from view. The entire scene—of raw ingredients to seasoned produce to the final form of Cantonese stir-fry—takes place in the middle of an alleyway, right in Hong Kong’s business district. Shelves with soy sauce, stacks of metal bowls, a large rice cooker, and one-and-a-half meter tall fridges form a circular, street-level assembly line. A plastic green tarp covers the makeshift kitchen, just in case it rains. There’s a small cutout of a Tsingtao box that hides a portion of the chef’s wok from me, but the smoke from his cooking clouds the air like mist. Sitting at a foldable dining table and a red stool, I can still smell him preparing the beef chow fun.

By some miracle, the entire restaurant is dismantled every evening, and reassembled once morning comes. When the kitchen is cleared from the street, dining tables are rolled to the side, and stools are stacked on the sidewalk. There’s a very scene-y nightclub that plays UK Garage every weekend three stories above the alley. By the time the club opens, the street that served food a few hours ago morphs into a kind of twilight zone, where partygoers rest their eardrums from the warped bass, take smoke breaks, and piss on concrete walls.

Known as “dai pai dongs,” open-air restaurants are a staple of Hong Kong, first emerging after WWII. The prevailing mythos goes that when families of deceased civil servants needed a way to earn money, the colonial government granted licenses for them to open makeshift, street-level restaurants. The practice has a scrappiness to it, an indeterminacy that reflects the city’s constant need to adapt to adverse environments.

Dai pai dongs, however, are also a vanishing practice. Over their seven-decade-long presence in the city, many have shut down due to government requirements, most often for hygiene controls. As a regular patron at these restaurants, I don’t doubt that cleanliness is not the main priority (over dinner, the only “dishwasher” I could see was a red plastic basin filled with plates, water being hosed into it as it lay on the pavement). But it’s a small price to pay for the wok hei—a complex charred flavor you can only taste when food is cooked in a piping-hot, kerosene-fueled wok.

In Hong Kong, only 17 of these open air restaurants remain. And the threat of disappearance has caused a surge in their popularity among the city’s tourists, residents, and (paradoxically) government officials. “Eating at a dai pai dong is a must-try Hong Kong experience,” reads one campaign from the local tourism board. “[And] you can’t call yourself a real foodie if you haven’t dined at one.”

What sets the dai pai dong apart is how it places its processes in full view. Seeing the food freshly made in front of you is just as (if not, more) important as receiving the dish itself. This dining experience gives the feeling that you’re witnessing a dying craft—not only because of attempts to standardize dai pai dongs into gentrified, indoor alternatives, but because witnessing the entire act of cooking feels out of place in an age of frictionless consumption.

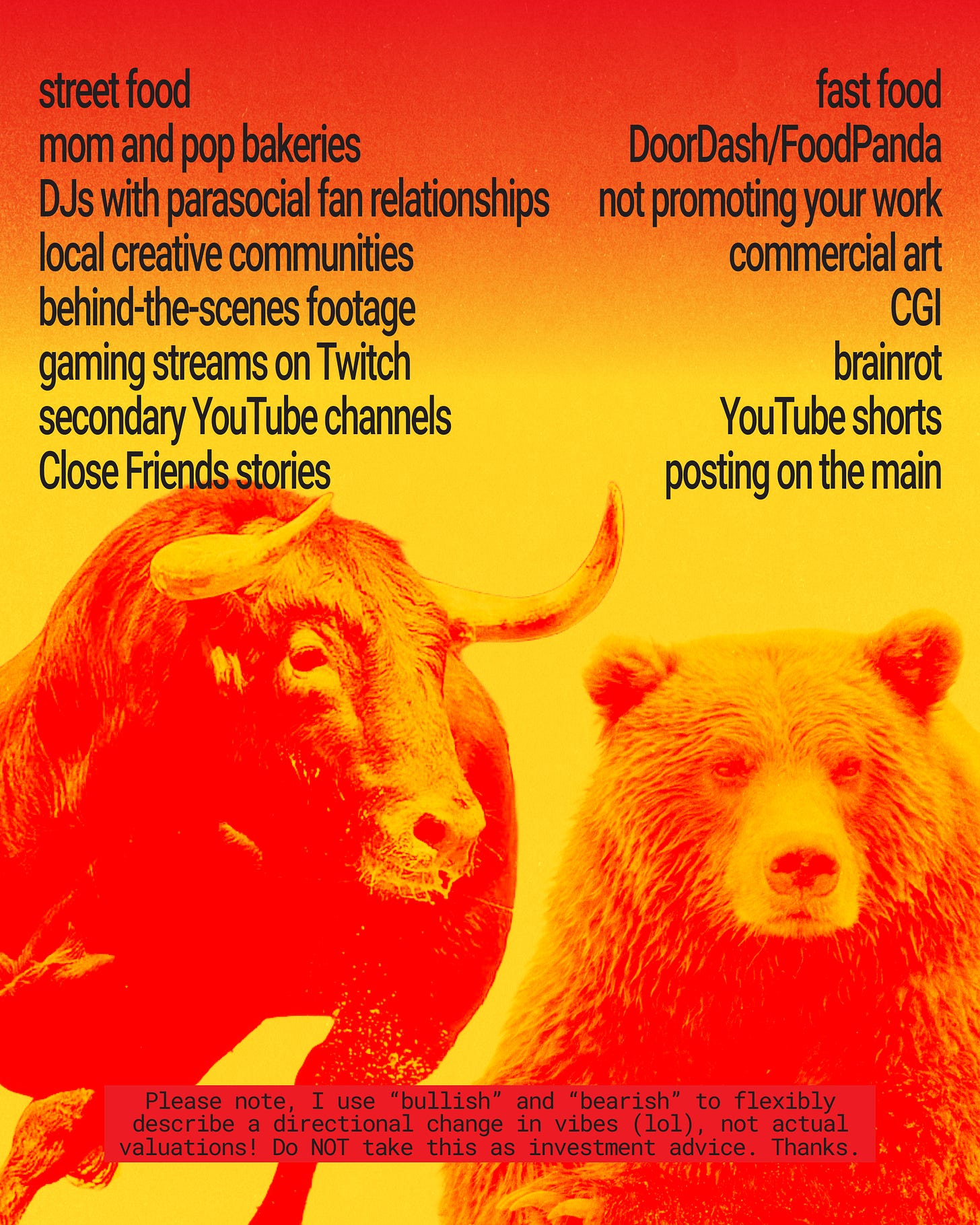

You could say that innovations from the last decade ran counter to the transparency an open-air kitchen offered. Food delivery apps, ride sharing platforms, farm-to-table produce, or even content recommendation algorithms all streamlined consumption, and hid the maker’s process from view: there are no sweaty old men in tank tops or checkered boxers; instead, the work is done by semi-anonymous drivers and deliverymen, or reduced to standardized, one-size-fits-all menus viewed through a phone. Brands like Whole Foods, DoorDash, Upwork, Netflix, and Uber all push what Alex Danco calls a “front of house / back of house” illusion, where abstraction was scaled as a business model.

But the new world we find ourselves in has the barrier to “making something” slashed to zero. Sora can generate a video for you in just a few minutes. ChatGPT can sputter a blog post in under thirty seconds. And that new app on the App Store could’ve been vibe coded in a handful of hours. For anyone “creating” and “producing,” there’s never been a greater burden to prove that your work is honestly yours. Case in point: last month, fans accused FKA twigs of using AI to create her EUSEXUA Afterglow album cover, despite the artist’s history of aversion to AI misuse: only a year ago, she had testified before the U.S. Senate to beg for artists’ protection from deepfakes.

When people are demanding honesty and transparency in how something is made, abstraction becomes a losing strategy. How can the real makers differentiate themselves from the slop farms and the junk factories?

We are returning to craft: new innovations aren’t obfuscating processes from us, but revealing them instead.

If you work in marketing, there’s a sense that behind-the-scenes campaign footage performs better than the actual campaign itself. When Apple released a new intro for Apple TV, featuring an animation with flipping colored glass, it was actually the video that documented the creative process—not the new intro itself—that performed better online. The craft, not the theatrics, stood out.

And recently, Resident Advisor argued in their RA PRO newsletter that since the COVID-19 pandemic, more electronic music producers are using social media platforms to share works-in-progress, asking fans for feedback, in part to prove that their work is human-made. Another example I’m a fan of was the viral Zoom meeting between A24’s brand marketing team and Timothee Chalamet. On YouTube, the video resonated because it was funny, but I also like to think that it gave a personalized, insider view into the eccentricities that come with making a film like Marty Supreme.

These examples only scratch the surface of the ways we’re returning to craft, or how deeply we crave processes to be made public. But travel across Asia and you’ll realize that this ethos has always existed. The case of dai pai dongs is unique to Hong Kong, but every country in the region has its variant of less-than-optimally-hygienic street food, where raw ingredients transform into local staples right in front of you. There are plenty of attempts to “modernize” them through hygiene controls, or by uprooting and gentrifying them. You can find a Singaporean hawker in an air-conditioned mall, or Vietnamese banh mi at an upscale restaurant. But in all cases, the older, less modern, less standardized form still survives. Often, it tastes better too. There’s a robustness to it that an app or a modernized kitchen simply cannot erase: recipes passed down from parent to child to grandchild, processes sharpened, honed, and refined over decades. What can we learn from this?

There will always be artisans who refuse to have their craft standardized, refuse to turn their process of work into a depersonalized abstraction. Many might imagine a world without them, but I’m optimistic that in the age of easy, mechanical reproduction, their work will be here to stay. Long life the craft.

https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/shop-class-as-soulcraft

Great article!